Steelhead trout numbers are staggeringly low across B.C., and conservationists are concerned a lack of data is only making matters worse.

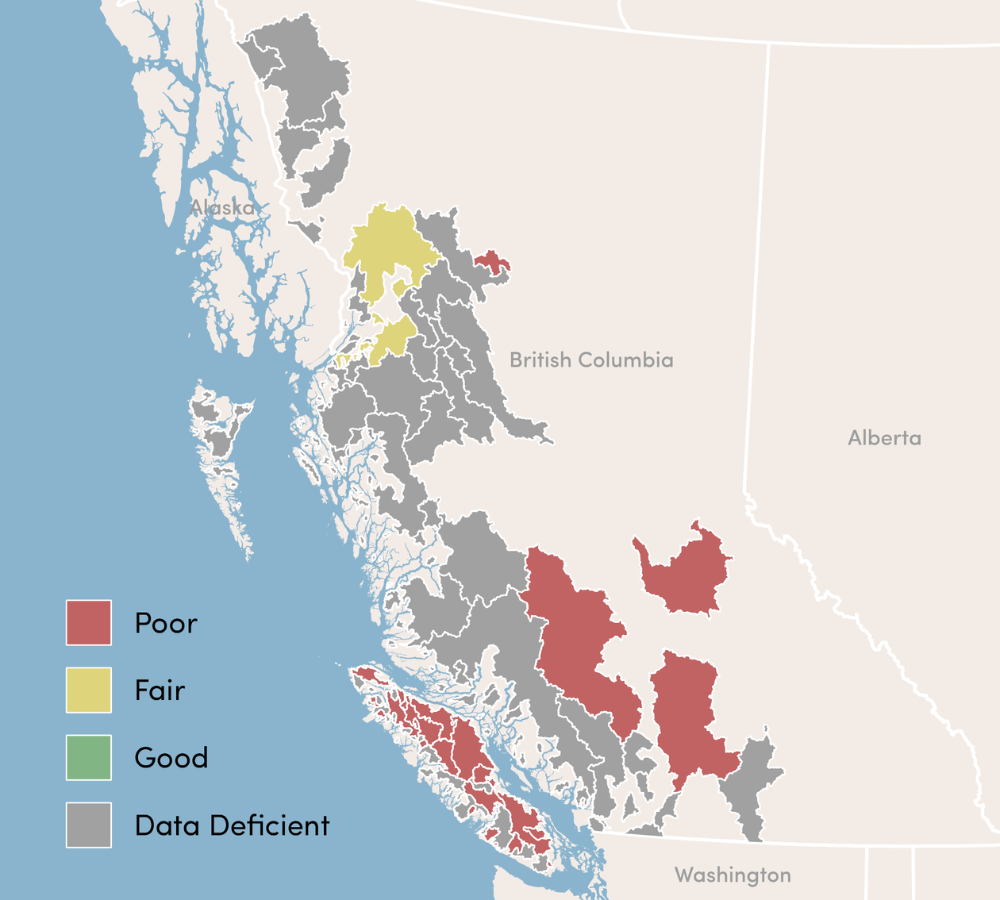

A new report from the Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) found that insufficient data sets are setting back conservation for steelheads in the province, with only seven of B.C.’s 36 distinct steelhead population groups containing sufficient data available to classify their conservation status.

Clare Atkinson, project manager of the Salmon Watersheds Program at the PSF, said the lack of data cuts the wings off conservation efforts.

“We’re trying to make sense of things when we only have part of the picture,” said Atkinson. “We’re essentially flying blind.”

Like other salmon species, steelhead spawn in freshwater, then travel out to the ocean for their adult lives. However, steelhead can spawn multiple times and migrate in both winter and summer runs, unlike other salmon.

Atkinson said steelhead are in a conservation grey area, often overlooked when it comes to overall salmon conservation. Though steelhead are a trout species, they share a common ancestor, similar migration routes and conservation challenges to other salmon species.

“The jurisdictional divisions between steelhead and salmon mean that they’re not always managed in a complementary way.”

Clare Atkinson, project manager of the Salmon Watersheds Program at the Pacific Salmon Foundation

“Depending on who you ask, steelhead are either included in the group called Pacific salmon or are considered a sort of lone species of trout, but steelhead share a lot of similarities to salmon, including a lot of the dynamics around their conservation. They also experience a lot of the same environmental pressures because they share habitats and follow a similar migratory pattern,” said Atkinson.

“But at the same time, the jurisdictional divisions between steelhead and salmon mean that they’re not always managed in a complementary way.”

With such a dearth of information, the PSF is concerned that steelhead could slip into a “silent extinction” if these concerning trends continue.

“No populations are in the green or good state, so overall it indicates that there is a pretty profound risk of local extinction of steelhead if action isn’t taken soon,” Atkinson said.

For the seven steelhead populations the PSF was able to classify in their report, all but one are in the “red zone,” or high conservation concern. The Nass River’s population was deemed “amber,” or fair, but Atkinson said they are still missing important information.

“Steelhead in the Nass may be faring slightly better. But it shouldn’t be considered conclusive evidence because, really, we lack data to assess most steelhead in northern B.C.,” she said.

While Atkinson could only speculate over why the Nass River’s population was more stable than others, she said that the remote nature of the watershed could be a contributing factor.

Steelhead in northwest B.C. hold high cultural importance for recreational anglers and First Nations.

They are often viewed as a dream catch, with recreational anglers flocking to the Skeena River from around the world to try their luck.

“Certainly in the Skeena watershed, the recreational steelhead fishery brings in a lot of economic activity to the region and is also sort of a cultural icon.”

Clare Atkinson, project manager of the Salmon Watersheds Program at the Pacific Salmon Foundation

Due to their year-round runs, steelhead are a historically important source of sustenance for Indigenous communities in the Northwest, while traditional fishing methods that have been practiced since time immemorial also hang in the balance.

“Certainly, in the Skeena watershed, the recreational steelhead fishery brings in a lot of economic activity to the region and is also sort of a cultural icon,” said Atkinson.

“And then there are many First Nations who practice traditional fishing techniques that are centered around steelhead, and obviously those practices rely on healthy and abundant steelhead populations to help cultivate those traditions into the future.”

The steelhead species seems to be more at-risk than other salmon species, though Atkinson again pointed to data gaps that make these assessments extremely challenging. She said steelhead are potentially more vulnerable to the impacts of warming oceans and degraded watersheds than other salmon species.

“On the one hand, there is a lot less information available on steelhead than salmon. On the other hand, the information that is available appears to indicate more profound declines among steelhead than salmon,” said Atkinson.

“And there are a variety of reasons that might be the case, including the fact that they spend more time in freshwater habitats and also might be more sensitive to warmer oceans. But it does appear that they may be sort of a canary in a coal mine in the sense that they may be one of the more sensitive species.”

“The first foundational step to moving forward and making informed decisions and actions is an improvement of the baseline information we have available.”

Clare Atkinson, project manager of the Salmon Watersheds Program at the Pacific Salmon Foundation

Another threat to the migratory trout in the Northwest is commercial fisheries in Southern Alaskan waters, where steelhead can be caught as bycatch while they are returning to their watersheds from the ocean. However, the perennial issue of a lack of data means the PSF cannot quantify what impact bycatch is having on the trout species, said Atkinson.

Implementing better funding and more monitoring of B.C.’s stock, particularly in remote areas, is the first priority for Atkinson and the PSF.

“The first foundational step to moving forward and making informed decisions and actions is an improvement of the baseline information we have available. This is sort of a first step towards cultivating that baseline common understanding of what’s happening.”

Information on B.C. steelhead and other salmon species can be found at the Pacific Salmon Explorer.

Story by Seth Forward, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter / TheNorthernView.com